Dilemma of US-China trade policy:

Balancing Prosperity and Inequality

Written by Yoochan Hwang, Year 11

The United States is grappling with the significant impacts of China's rapid increase in global prominence. The US trade deficit, reaching $621 billion in 2018 and $419.2 billion with China (Deaux et al., 2018), instigates the Trumpian trade war, which has "taken a sledgehammer" (Feng, 2020) to US-China relations, breaking off from its bilateral trade. After President Biden stepped in, the U.S. government employed measures like tariffs and investment restrictions to limit China's access to U.S. markets, balancing economic considerations and national security priorities. It is argued in this essay that Biden's trade policies, especially the national security measures, should clearly define its boundaries for sensitive technologies and goods, providing policy insights into how the United States will capitalize on the advantages of free trade and foster mutually beneficial trade relationships with China while protecting the state's competitiveness and national security.

In the past 50 years, globalization has significantly increased trade volume and the flow of capital, labor, and goods across borders. The rising trade due to the advancement in technologies and logistics has increased the interconnectedness between countries around the world, and the US’s overgrowing change in FDI is clearly illustrated in Fig. 1. Furthermore, as China joined the WTO in 2001, already a prominent trading partner of the US, globalization again irreversibly strengthened itself.

Fig. 1. U.S. Direct Investment Abroad and Foreign Direct Investment in the United States, Annual Flows, 1990-2016

(CRS Reports, 2017). U.S. Direct Investment Abroad: Trends and Current Issues, 2017)

However, China’s rise in the world free trade regime sowed seeds of conflict and concern. Over the past two decades, China has deeply integrated into the world economy, and today it is the largest supplier of manufactured goods. From its global GDP share of 7.23% in 2000, it showed a tremendous increase to 16.68% in 2018. As a result, the US was concerned about China’s increasing global prominence. To exemplify, the US’s increasing trade deficit with China recorded $419.2 billion in 2018 (Deaux et al., 2018), and China’s unfair trade practices, such as the theft of intellectual property (IP) and trade secrets from U.S. businesses, raised tension between the US and China. In response, former President Donald Trump marked the starting point of the trade war, introducing it as "good and easy to win” (Deaux et al., 2018), beginning to impose duties on Chinese products ranging from 3.1 to 21 percent from 2018 to 2020 (Mishra, 2022) to slow China's growth. While Trump’s China policy's primary focus is on 'Making America Great Again' (MAGA) logic, President Biden redirected his focus toward'strategic competition' (Mishra, 2022), encompassing both economic and national security issues such as the 2022 ban on chip-making equipment exports and limiting China’s ability to import US processors from AMD, Intel, and others. In this aspect, The Interim National Security Guidance (2021), published by the White House, states that America will "join with like-minded allies and partners to revitalize democracy the world over" and to "out-compete a more assertive and authoritarian China over the long-term [by] investing in their people, economy, and democracy" (Biden, 2022).

To fairly evaluate the consequences of the trade war, we must also judge whether the US-China trade relations before it were truly detrimental to the US’s interests. In the early 2000s, the United States and China entered into a mutually beneficial relationship, solidifying their status as permanent trading partners, which significantly contributed to their growth and aggregate gain. A macro-level analysis by the Eaton & Kortum (2002) model, or a monopolistic competitive model by Krugman (1980) and Melitz (2003), demonstrates the positive outcomes of free trade for the US, illustrated in Figure 2. Caliendo and Fernando (2023) provide evidence that the US-China trade (1995–2011) resulted in mutually beneficial outcomes, with the United States and China experiencing an aggregate gain of 3.39% and 4.58%, respectively.

Fig. 2: Aggregate gains from US-China trade (1995–2011)

Data from the World Input-Output Database from 1995 to 2011 (https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/valuechain/wiod/). See Timmer et al. (2015) for more information.

Although the bilateral trade between China and the US had inarguably contributed to the aggregate welfare of both countries and provided consumers with cheaper imports, it marked heterogeneity in welfare impact across different industries, creating winners and losers. Caliendo and Fernando (2023) quantify the general equilibrium effects of the China shock, finding that increased Chinese import competition reduced aggregate manufacturing employment share by 16% from 2000 to 2007, or about 0.55 million manufacturing jobs. However, non-manufacturing industries such as construction, wholesale, and retail showed an incline in production as they imported cheap intermediate goods from China, and “US manufacturing firms expanded their non-manufacturing employment in response to import competition from China.” (Fort et al., 2018, 68).

However, contrary to the common belief about the negative impact of free trade, studies show that the decline of US businesses is not entirely due to China but to the US itself. Chakravorty and his colleagues (2017) find nonsignificant effects of Chinese import competition on patent count and positive effects on citation-weight patents. In particular, for comparison, Bloom and colleagues (2015) suggest that from 2000 to 2007, “import competition from Chinese firms accounted for almost 15% of the increase in patenting, information technology spending, and productivity (Caliendo & Fernando, 2023) in European countries. On the contrary, the US industry displays larger gaps in the technological capabilities of leading and lagging firms; thus, the rising competition with China's negative impact concentrated on initially less productive and less profitable firms, creating the illusion that the Chinese imports are killing the domestic businesses in aggregate. Moreover, the workers displaced in the manufacturing sector could switch to other jobs, either by switching firms or industries or by migrating to other regions. In other words, workers can overcome the mobility friction in the long run.

Despite the overall welfare implications, scholars have criticized free trade for its unequal distribution effect. In this vein, it is crucial to speculate if the trade war has achieved its intended purposes and is economically justifiable. Overall, there is a general agreement that the trade war caused a negative welfare impact. First, the Trumpian tariff, which was “unprecedented in terms of the scope and magnitude of tariff change(Irwin, 2017), increased from 3.7 to 25.8%, leading China to respond with retaliatory tariffs on $100 billion of imports along with other trade partners, which raised its average tariff from 7.7% to 20.8% (Fajgelbaum & Khandelwal, 2022).

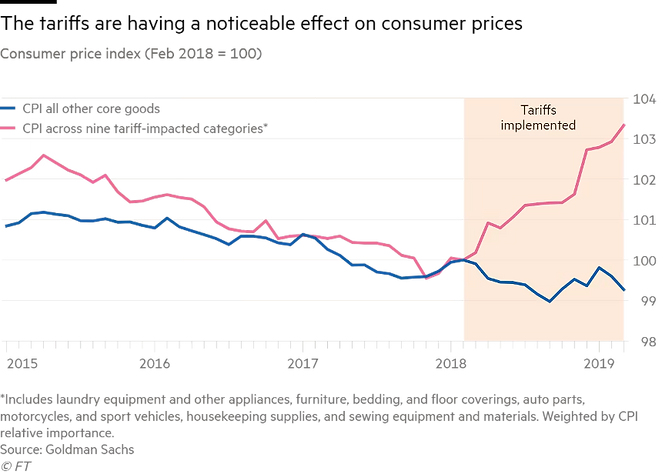

Thus, far from its aim to save the manufacturing industry from unemployment and ameliorate distribution impact, the import protection for the US manufacturing industry was offset by larger negative effects from retaliatory tariffs. Moreover, the rising cost of intermediate goods and inputs was one of the biggest contributors to rising unemployment. (Flaaen&Pierce,2019). According to Flaaen and Pierce (2019), the textile industry, which was one of the biggest losers throughout China Shock, was actually the biggest winner during the trade war, but industries such as computer electronics and furniture experienced an almost 40% decline. The change in tariff impacted 84% of US exports and 65% of manufacturing employment, resulting in an extra cost of 900 dollars per worker (Handly et al., 2020). Moreover, Caliendo and Parro (2022) find that US household welfare declined by 0.1% in aggregate due to the trade war compared to a 0.2% increase in China shock. The full trade war had no impact on reversing the decline in manufacturing sector employment; in fact, it caused a decline of 0.03 percent. Eventually, the Trumpian trade war was not effective in fostering more employment in either the manufacturing or non-manufacturing sectors. Using monthly US Census data collected from 2017 to 2018 on import quantities, Amiti et al. (2019) and Cavallo et al. (2021) document that the increase in US import tariffs was almost fully passed through to total prices paid by importers and their consumers. As shown in the graph below, the CPI of tariff-impacted categories rose significantly throughout the trade war era, while the CPI of all other goods showed a general decline. Consequently, the Trumpian trade war only reversed the losers and winners from each policy, failing to “make America great again” in aggregate.

Fig. 3: Average US CPI Change 2015-2019

Financial Times. (2019). (US consumers start to pay the price of the trade war with China, 2019)

It is worth noting that free trade gives rise to tensions between efficiency (in the Kaldor-Hicks sense) and distribution. To define Kaldor-Hicks efficiency, an outcome is efficient if those who are made better off could, in theory, compensate those who are made worse off, producing a Pareto efficient outcome. (Rauterberg,1940) Therefore, even if we focus on a single efficient policy change and perceive that it has troubling distributional consequences for some sectors, we must ask whether a further policy change can remedy the distributional problems to our satisfaction without sacrificing any industries. Therefore, based solely on the perspective of efficiency, one can argue that free trade policy is superior to protectionist measures in an economic sense. Data also supports the claim.

Tracking the progress of the Biden administration’s new China policy, it is evident that American-China trade volume went down. However, despite Joe Biden’s aim to decouple China and protect national security, America has been unable to stop China’s rising global prominence, failing to convince its allies to reduce China’s role as the world’s largest supplier. Ironically, the decoupling strategy may be forging stronger financial and commercial connections between China and America’s allies, receiving Chinese investment and intermediate goods, contrary to the policy’s main objective. As shown in Fig. 4, since 2016, the U.S. and China have substantially reduced their focus on flows of trade, capital, information, and people with each other. In some areas, such as imports and scientific research collaboration, U.S. allies have even increased the share of their flows with China and its allies (Altman, 2023). Thus, President Biden’s China strategy has, in fact, enhanced the possibility of taking sensitive technology from the US and US alliance easier, failing to make an impact on national security. After the new regulations regarding chips and sensitive technologies, for example, firms panicked over worsening relations across the Pacific and pursued alternatives such as Vietnam. Yet American demand for final products from allies also boosts demand for Chinese intermediate inputs, and China’s role as the cheapest, irreplaceable supplier led many poorer countries to receive Chinese investment and intermediate goods and export the finished products to America.

Fig. 4: Allied countries flow shares (Altman (2023), The State of Globalization in 2023.)

In conclusion, the Biden administration's approach to national security concerns is crucial to adopting a more targeted strategy. While protecting critical aspects of America's sensitive technologies is undoubtedly important, the measures taken should be carefully calibrated to avoid having negative influences on other sectors. Thus, the crucial technologies for the US’s potential growth in the future, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, robotics, and quantum computing (Williams, 2018), must be tightly controlled. However, some other industries that don't raise any national security concerns but were heavily affected by tariffs, such as furniture, should enjoy the benefits of free trade. Furthermore, future trade policy should concentrate on regaining mutually beneficial relationships rather than creating rivalries to tackle the trade imbalance and China’s growing power. By doing so, the revival of the US-China relationship and bilateral trade will simultaneously nurture both nations’ global prominence and economic growth, benefiting all firms, consumers, and workers.

References:

========================================================================

Deaux, J., Mayeda, A., Olorunnipa, T., & Black, J. (2018). Trump Says Trade Wars

Are 'Good and Easy to Win.’ Bloomberg.com.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-01/trump-is-said-to-delay-decisio

n-on-steel-and-aluminum-tariffs

Feng, H. (2020). Trump took a sledgehammer to US-China relations. This won’t be

an easy fix, even if Biden wins. The Conversation.

https://theconversation.com/trump-took-a-sledgehammer-to-us-china-relations-this-w

ont-be-an-easy-fix-even-if-biden-wins-147098

CRS Reports. (2017). U.S. Direct Investment Abroad: Trends and Current Issues.

(2017, June 29). CRS Reports.

https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RS21118.html#_Toc486603471

Vivek Mishra (2022). From Trump to Biden, Continuity and Change in the US’s China

Policy. ORF Issue Brief No. 577, September 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

President Joseph R. Biden Jr (2021). The Interim National Security Guidance, pp

Krugman P. (1980). Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of

trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 70(5):950–59

Melitz MJ. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate

industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1695–725

Caliendoo & Parro (2023). Lessons from US–China Trade Relations. The Annual

Review of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics- 082222-08201

Fort TC, Pierce JR, Schott PK. (2018). New perspectives on the decline of US

manufacturing employment. J. Econ. Perspect. 32(2):47–72

Chakravorty U, Liu R, Tang R. (2017). Firm innovation under import competition from

low wage countries. CESifo Work. Pap. Ser. 6569, CESifo, Munich

Bloom N, Kurmann A, Handley K, Luck P. (2019). The impact of Chinese trade on

U.S. employment: the good, the bad, and the apocryphal. Paper presented at the

2019 Meeting of the Society for Economic Dynamics, St.Louis, MO, June 27–29

Handley. (2020). Rising Import Tariffs, Falling Export Growth: When Modern Supply

Chains Meet Old-Style Protectionism. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Working paper 26611. doi: 10.3386/w26611

Irwin DA. (2017). Clashing Over Commerce: A History of U.S. Trade Policy. Chicago:

Univ. Chicago Press Johnson RC, Noguera G. 2012. Accounting for intermediates:

production sharing and trade in value added. J. Int. Econ. 86(2):224–36

Fajgelbaum PD, Khandelwal AK. (2022). The economic impacts of the US–China

trade war. Annu. Rev. Econ. 14:205–28

Flaaen A, Pierce JR. (2019). Disentangling the effects of the 2018–2019 tariffs on a

globally connected U.S. manu-facturing sector. Finance Econ. Discuss. Ser.

2019-086, Board Gov. Federal Reserve Syst., Washington,DC

Amiti M, Redding SJ, Weinstein DE. (2019). The impact of the 2018 tariffs on prices

and welfare. J. Econ.Perspect. 33(4):187–210

Cavallo A, Gopinath G, Neiman B, Tang J. (2021). Tariff pass-through at the border

and at the store: evidence from US trade policy. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 3(1):19–34

Rauterberg, G. (2016). THE CORPORATION’S PLACE IN SOCIETY [Review of

Morality, Competition, and the Firm: The Market Failures Approach to Business

Ethics, by J. Heath]. Michigan Law Review, 114(6), 913–928.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/24770890

Altman, S. A. (2023). The State of Globalization in 2023. Harvard Business Review.

https://hbr.org/2023/07/the-state-of-globalization-in-2023

Williams. (2018). Protecting sensitive technologies without constricting their

development | Brookings,

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/protecting-sensitive-technologies-without-constrict

ing-their-development/